Hardware

Checklist

Have you provided links to your original design files for your hardware on the product itself or its documentation?

Have you made it easy to find your original design files from the website for a product?

Have you clearly indicated which parts of a product are open-source (and which aren’t)?

Have you applied an open source license to your hardware?

After certification, remember to:

- Label your hardware with a version number or release date, so people can match the physical object with the corresponding version of its design files.

- Use the OSHWA certification mark logo on your hardware. Do so in a way that makes it clear which parts of the hardware the logo applies to (i.e. which parts are open-source).

About

In order for your project to be OSHWA-certified, you need to attach an open source license to the hardware components. This license will provide the specific permissions and information downstream users need to make, use, remix, and build upon your work.

Licensing hardware is more complicated than licensing software. Software automatically receives copyright protection upon creation, which makes licensing relatively straightforward. By contrast, hardware has more moving pieces to consider. Your hardware project will likely contain software, documentation or branding – each of which may be protected by a different category of intellectual property law.

There are three main intellectual property regimes that may offer some protection to your project: copyright, trademark, and patent law. However, these regimes may not necessarily protect every component of your hardware.

- Copyright law offers protection for “original works of authorship” which are “fixed in a tangible medium.” This means that original and creative elements of your product may be protected by copyright law. This does not include functional elements of your product.

- Trademark law protects “source identifiers”, which may include any brand names, product names, logos, or even the design and packaging of your product (more on this later).

- Patent law protects functional inventions that are “novel” and “nonobvious”, when the inventor applies for protection from the US Patent & Trademark Office.

To the extent that your hardware may be protected by one or more of these IP regimes, properly applying an open source hardware license to your project ensures that downstream users can use your product within the bounds of your license. These regimes will not protect every element of your hardware:

- Copyright: While certain hardware elements might be creative, the creativity is often constrained by functionality, which prevents most physical aspects of most hardware from being protected by copyright. For example, the way in which parts of a 3D printer’s extruder work together is governed by functional concerns. That means that it cannot be protected by copyright law.

- Trademark: While trademark law may protect the names, logos, and other elements that signal who the producer of the product is, in most cases trademark law do not protect the physical object itself.

- Patent: The requirement that functional inventions be “novel” and “nonobvious” are high legal bars that few inventions meet. Additionally, patents are very expensive to obtain and the process is quite complicated, usually requiring help from specialized lawyers. You must take affirmative steps to obtain patent protection for your hardware.

Regardless of how and to what extent these various types of IP protections apply to your specific hardware, it is important to apply the appropriate open source license to each element of your project. Doing so will enable downstream users to legally utilize your work. The terms of the license will signal to users how you would like them to use your hardware.

It is important to keep in mind that your hardware may not be fully protected by all—or any—of these IP rights. That means that a hardware license may do little to prevent bad actors from simply recreating unprotected components of your hardware projects and using them for purposes you do not approve of. It also means that licenses that require users to make their contributions open may not be legally enforceable. However, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t license at all. It is best to think of hardware licenses as guiding tools for good actors, not ways to punish bad actors.

Checklist

Have you provided links to your original design files for your hardware on the product itself or its documentation?

Have you made it easy to find your original design files from the website for a product?

Have you clearly indicated which parts of a product are open-source (and which aren’t)?

Have you applied an open source license to your hardware?

After certification, remember to:

- Label your hardware with a version number or release date, so people can match the physical object with the corresponding version of its design files.

- Use the OSHWA certification mark logo on your hardware. Do so in a way that makes it clear which parts of the hardware the logo applies to (i.e. which parts are open-source).

Spectrum

The scope of copyright protection is limited to strictly decorative components of hardware. As a result, at a baseline level, the hardware for many functional open source hardware products will not be protected at all. Copyright protection will begin to attach only as decorative and aesthetic elements are added to the hardware.

Whether a particular hardware design or design element is covered by copyright is not always a simple yes/no question. Instead, the range of copyright protectability of hardware tends to vary on a spectrum that is closely linked to the hardware’s functionality. The more the hardware’s design is driven by functional concerns, the less likely it will be protected by copyright; the less the hardware’s design is driven by functional concerns, the more likely it will be protected by copyright.

The spectrum below shows the range of protectability of various exemplary products. Hardware towards the left side of the spectrum is mostly or exclusively functional, meaning it receives little or no protection under copyright law. As you move across the spectrum, the hardware integrates an increasing number of non-functional, creative design elements, increasing the hardware’s protectability under copyright law. It’s important to keep in mind that this protection will never extend to any purely functional components of the hardware. However, in some cases—for example, when decorative or aesthetic features extend across the entire product, or when a decorative or aesthetic feature is essential to the product’s appeal to users, this protection can effectively control reproduction of the entire physical product.

Less

Protectable

More

Protectable

Open Source Laboratory Sample Rotator and Mixer

This product is a 3-D printable laboratory sample rotator-mixer designed for tumbling and gentle mixing of laboratory samples. This design easily allows for a variety of mixing angles and features a convenient angle changing mechanism.

The physical design choices that were made in constructing this product were driven almost exclusively by functional motivations. As a result, the hardware does not incorporate creative design elements that are unrelated to the core functionality of the product. Thus, the hardware itself is very unlikely to be eligible for copyright protection.

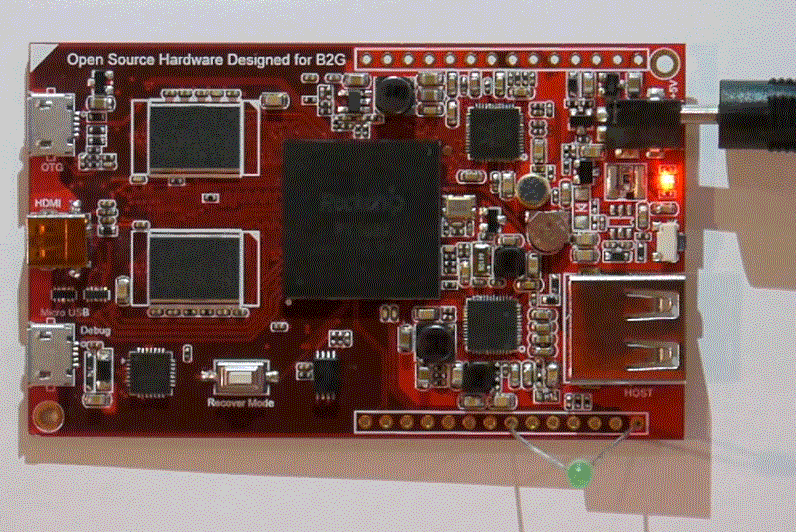

Chirmen

The Chirmen is made up of a number of complex technical elements. The requirements of those technical elements - not creative decisions by the team - define its physical appearance. As such, it is unlikely that the Chirmen’s physical hardware is protected by copyright. This lack of copyright protection for Chirmen’s hardware does not reduce the copyright protection that would apply to any software incorporated into the hardware.

Neurobite

The Neurobite’s physical layout is almost entirely dictated by the functional requirments of the PCB. However, the team has incorporated an image of a neuron and centered it on the LED. This arguably gives it a low level of copoyright protection, so it is wise for the team to include a permissive copyright license for the hardware.

ECG Patient Simulator

This product tests the accuracy and performance of an Electrocardiogram (ECG) cable. The ECG Patient Simulator generates an ECG signal similar to that of a perfectly connected patient and is used to compare the strength of the signal before and after the cable is connected to the patient.

The physical design of this product is largely derived from the functional components of hardware. Nevertheless, there are some aesthetic design elements incorporated into the hardware that may warrant some copyright protection of those elements, such as the ECG wave in the center of the product, the bright orange color, and the distinctive color of each knob’s assigned letter.

AXIOM Case

The shape and featureds of the axiom case are mostly dictated by the functional necessity of housing the core elements, providing ventilation, and connecting accesories. Nonetheless, the team has made creative decisions around how to shape the ventilation, as well as the contrast piece and notch on the side. This creates at least the potential that the case itself may have some level of copyright protection.

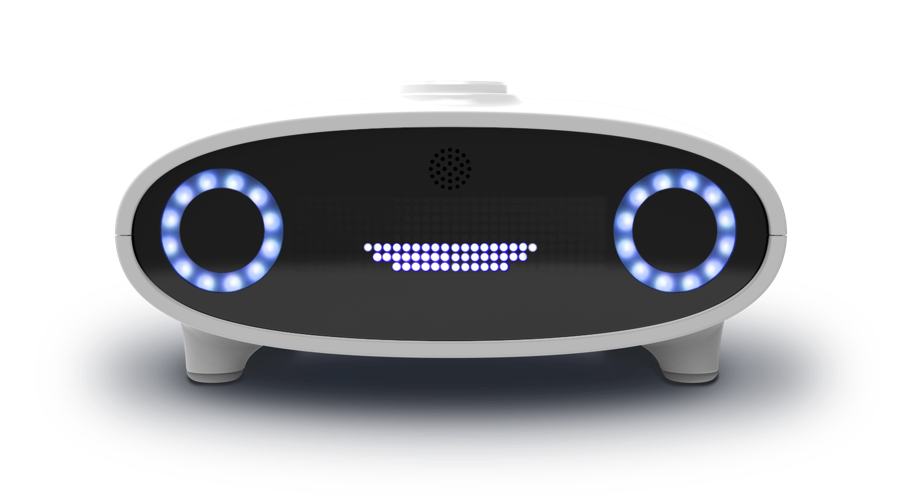

Mycroft Mark 1

The Mycroft Mark 1 incorporates functional elements such as status lights into a whimsical and decorative case that evokes the face of a friendly robot assistant. This creative presentation of functional elements is eligable for copyright protection.

Voidbox Concrete Business Card Holder

The Voibox business card holder goes well beyond what is technically necessary to simply hold a business card on a desk. The creative and decorative sculptural elements make it easily protected by copyright.

Voidbox Hactus

The Hactus is a traditional prototyping board with a unique aesthetic twist. The product uses interlocking green perfboards boards inside a flowerpot to embody the visual representation of a succulent cactus.

The physical appearance of this product is entirely dictated by creative and aesthetic design choices. Prototyping boards are used to affix electronic components to build a circuit, something that does not require the product to resemble a succulent. Therefore, the imaginative and artistic design elements make it easily protected by copyright.

Checklist

Have you provided links to your original design files for your hardware on the product itself or its documentation?

Have you made it easy to find your original design files from the website for a product?

Have you clearly indicated which parts of a product are open-source (and which aren’t)?

Have you applied an open source license to your hardware?

After certification, remember to:

- Label your hardware with a version number or release date, so people can match the physical object with the corresponding version of its design files.

- Use the OSHWA certification mark logo on your hardware. Do so in a way that makes it clear which parts of the hardware the logo applies to (i.e. which parts are open-source).

Licensing

Licensing each element of your project is an essential part of obtaining OSHWA certification for your project. The range of protectability of hardware varies on a spectrum, with some hardware projects that are very likely to be protected by copyright, some that are not, and others that are somewhere in the middle. Regardless of where your hardware project falls on this spectrum, it is still required to have an open source license, addressing any copyright and other intellectual property rights that cover your project, attached to the project in order to receive OSHWA certification.

With a properly defined open source license, you assure the public that your project is truly “open source” for others to use, distribute, and modify. The license guarantees downstream users the freedom to use and modify your work without needing additional permissions. It also tells downstream users exactly what they can and cannot do with your invention – while also giving you, the original creator, credit for your contributions!

There are several OSHWA-approved open licenses that you can choose from. Read through the most common ones below and choose what’s best for your hardware project.

Checklist

Have you provided links to your original design files for your hardware on the product itself or its documentation?

Have you made it easy to find your original design files from the website for a product?

Have you clearly indicated which parts of a product are open-source (and which aren’t)?

Have you applied an open source license to your hardware?

After certification, remember to:

- Label your hardware with a version number or release date, so people can match the physical object with the corresponding version of its design files.

- Use the OSHWA certification mark logo on your hardware. Do so in a way that makes it clear which parts of the hardware the logo applies to (i.e. which parts are open-source).

Recommended Licenses for Hardware

CERN-OHL-P-2.0

The CERN Open Hardware License Version 2.0 - Permissive is a license developed by CERN to promote collaboration among hardware designers and to provide a legal tool which supports the freedom to use, study, modify, share and distribute hardware designs and products based on those designs.

Version 2 of the CERN OHL comes in three flavors with different levels of permissiveness: the P permissive flavor, the W weakly reciprocal flavor, and the S strongly reciprocal flavor. All three versions are designed to include all of the rights associated with an open hardware project, including hardware, software, and documentation.

The P version is designed to be broadly permissive for users and is conceptually similar to the Apache 2 open source software license.

CERN-OHL-S-2.0

The CERN Open Hardware License Version 2.0 - Strongly Reciprocal is a license developed by CERN to promote collaboration among hardware designers and to provide a legal tool which supports the freedom to use, study, modify, share and distribute hardware designs and products based on those designs.

Version 2 of the CERN OHL comes in three flavors with different levels of permissiveness: the P permissive flavor, the W weakly reciprocal flavor, and the S strongly reciprocal flavor. All three versions are designed to include all of the rights associated with an open hardware project, including hardware, software, and documentation.

The P version is designed to impose strong reciprocal obligations on users and is conceptually similar to (although not compatible with) the GPL3 open source software license.

CERN-OHL-W-2.0

The CERN Open Hardware License Version 2.0 - Weakly Reciprocal is a license developed by CERN to promote collaboration among hardware designers and to provide a legal tool which supports the freedom to use, study, modify, share and distribute hardware designs and products based on those designs.

Version 2 of the CERN OHL comes in three flavors with different levels of permissiveness: the P permissive flavor, the W weakly reciprocal flavor, and the S strongly reciprocal flavor. All three versions are designed to include all of the rights associated with an open hardware project, including hardware, software, and documentation.

The P version is designed to impose weakly reciprocal obligations on users and is conceptually similar to the LGPL3 open source software license.

Solderpad

The Solderpad Hardware License is a wraparound license that takes an open source software license and modifies it for the hardware context.

The Solderpad license is a permissive license, meaning that downstream users are free to use, copy, and modify hardware projects licensed under the Solderpad license without imposing any reciprocal obligations. Downstream users that modify the open source hardware project are not required to make those modifications available on the same open terms of the original project.

TAPR

The Tusan Amateur Packet-Radio Open Hardware License (TAPR OHL), created in 2007, was the first hardware-specific open source license. It was developed specifically in the context of the amateur radio community to help these hobbyists share their hardware designs with fellow enthusiasts. The TAPR OHL is the first open source license that accounts for the physical product, like a piece of hardware, and its supporting design documentation in the license terminology.

The TAPR OHL is a reciprocal license, meaning that downstream users are free to use, recreate, and modify open source hardware projects licensed under TAPR OHL, so long as they continue to keep the project accessible under the same TAPR license.

Examples of Hardware Licensing

Johan Smets ECG Patient Simulator

Hardware License:

CERN-OHL-S-2.0

Why this license?

The CERN OHL v2.0, S Variant, will allow downstream users to copy and modify these aesthetic design elements without fear of infringement. The S Variant of this license will additionally impose reciprocal obligations on downstream users. For example, if a downstream user takes this product and makes any modifications, they will be obligated to make the modified design available to the public under the same CERN OHL v2.0, S Variant license.

Kolibri HALO-90

Hardware License:

CERN-OHL-S-2.0

Why this license?

The CERN OHL v2.0, S Variant, will allow downstream users to copy and modify these aesthetic design elements without fear of infringement. The S Variant of this license will additionally impose reciprocal obligations on downstream users. For example, if you take this product and make modifications – such as change the color of the LED light, or add a second ring of light to the earring that has a synchronized light pattern – you are obligated to make those modifications available to the public under a CERN OHL v2.0, S Variant license.

Apertus AXIOM

Hardware License:

Why this license?

The AXIOM’s internal hardware is mostly functional and is therefore unlikely to be protected by copyright. However, the cases and other external elements incorporate a number of creative elements protectable by copyright. The CERN license will allow users to copy and modify the parts without fear of infringement.

Public Lab Papercraft Spectrometer Intro Kit

Hardware License:

Why this license?

Although the form of the spectrometer is mostly functional, the graphical designs are protected by copyright. The CERN license establishes the terms by which others can copy and build upon the existing hardware without violating copyright.

OpenAir Cyan

Hardware License:

CERN-OHL-P-2.0

Why this license?

As a predominately functional product with very minimal aesthetic design elements, this product is unlikely to receive copyright protection. However, without an open source license, if people were to come across the product’s design and were curious about creating their own to have first-hand experience with carbon removal, they might be hesitant to actually recreate the device for fear of legal liability. The CERN OHL v2.0, P Variant license overcomes that barrier. Not only does it assure the public that the product is truly “open” for public use, the P Variant also doesn’t require downstream users to apply the same license to any modifications they make to the product’s design – something that can also hinder public use.

Checklist

Have you provided links to your original design files for your hardware on the product itself or its documentation?

Have you made it easy to find your original design files from the website for a product?

Have you clearly indicated which parts of a product are open-source (and which aren’t)?

Have you applied an open source license to your hardware?

After certification, remember to:

- Label your hardware with a version number or release date, so people can match the physical object with the corresponding version of its design files.

- Use the OSHWA certification mark logo on your hardware. Do so in a way that makes it clear which parts of the hardware the logo applies to (i.e. which parts are open-source).

Commercialization

Hardware can be difficult to protect with intellectual property rights, so enforcement of open source rules can be challenging.

Ensure that your trademark- and copyright-protection is strong.

Consider making your product available as a DIY kit, which are very popular. Because of their value as teaching tools, DIY kits have become very popular as a method of creating markets for things such as consumer electronics. For example, consider the popularity of kits such as Sparkfun, and Arduino. The creation of DIY kits serves as useful entry point into the market for open source hardware products.